Restored copy by Lithuanian Film Center in collaboration with Lithuanian Culture Institute

On the 100th anniversary of the birth of Jonas Mekas, the father of the New American Cinema who was celebrated right here in 1966, the Pesaro Film Festival screens the world premiere of the restored As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, in collaboration with the Lithuanian Film Centre and the Embassy of Lithuania in Italy, in the framework of the official celebrations organized by the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture.

“My film diaries 1970-1999. It covers my marriage, children are born, you see them growing up. Footage of daily life, fragments of happiness and beauty, trips to France, Italy, Spain, Austria. Seasons of the year as they pass through New York. Friends, home life, nature, unending search for moments of beauty and celebration of life – friendships, feelings, brief moments of happiness, beauty. Nothing extraordinary, nothing special, things that we all experience as we go through our lives. There are many inter-titles that reflects my thoughts of the period. The soundtrack consists of music and sounds recorded mostly during the same period from which the images came. Sometimes I talk into my tape recorder, as I edit these images, now, from a distance of time. The film is also my love poem to New York, its summers, its winters, streets, parks. It’s the ultimate dogme movie, before the birth of dogme.” (Jonas Mekas)

sceneggiatura/script Jonas Mekas

fotografia/cinematography Jonas Mekas

montaggio/edit Jonas Mekas

musica/music Auguste Varkalis

interpreti/cast Jonas Mekas, Jane Brakhage, Stan Brakhage, Robert Breer, Hollis

Frampton, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Kubelka, Nam June Paik, P. Adams Sitney

The adjective “Brief” in [the film’s] long title indicates that the visions of beauty we see through the filmmaker’s eyes flicker against a darker, invisible horizon. Emphasizing that he speaks from the time of editing, many years, even decades, after most of the material was shot, he addresses us as his friends while he sits alone, always late at night, assembling the film.

At nearly five hours As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty is by far his longest diary film. Astonishingly, on the threshold of his 80th year, Mekas has given us his most moving and most exuberant film. He lets us know as he speaks from within the film that, overwhelmed with the footage he has amassed, he resigned himself to assembling the film largely by chance, putting images of his family life willy nilly in twelve chapters. Yet one-third of the way through, he advises his viewers to read the film carefully, to interpret what he is showing us, even though later he will contend that these images are immediately transparent, that they mean only themselves. Contradictions of this sort abound in As I Was Moving Ahead…; its voice-over text is the richest and most complex the filmmaker ever attempted. Eventually, the speaking “I” powerfully addresses a sequence of beings he calls “you” over the course of the film. Cumulatively, these speeches sketch out a series of triadic relationships (e.g. “I,” “you,” the film images) which generate the dialectical interactions between chapters.

At several points in this unusually abundant and speculative voice-over commentary, Mekas insists that this is a film about nothing, in fact, “a masterpiece of nothing.” The refusal of chronological development, the repetition of intertitles, the voice-over emphasis on both moments of ecstasy and involuntary memories, and the sheer duration of the film deliberately prevent us from quickly grasping its overall form or easily charting its development.

Each chapter re-examines the joys of daily living and wonders at its evanescence; each chapter introduces new material, slightly altering the authorial perspective while asserting continuities with the previous chapters. Eventually, the rhythmic alternation of chapters articulates the crisis dynamic of the film as a whole. Usually Mekas speaks on the soundtrack near the start of a chapter to comment on the progress, or the nothingness, of the film so far. Often he laughs at himself, and at his self-consciousness as he talks to his viewers.

[…] The title, reinforced by its punctuating voice-overs, insists that flashes of exhilaration have irradiated the continuous passage of his life, “one epiphany after another,” as David James described Mekas’s style.1 The stress on the gravity of these moments not only describes his signature mode of filming but also suggests that the illuminations of beauty and happiness stand out against the background of sustained anguish. In the first chapter we read the intertitle: “about a man whose lip is always trembling from pain and sorrow experienced in the past which only he knows –.” Significantly, an image of the filmmaker, playing the bayan, immediately precedes this intertitle. Mekas, as Orpheus, sings a wordless song over these images and over the subsequent shots of rain and lightning. He is still singing when a more anecdotal intertitle follows: “I remember the morning I passed Avignon…” The cause and nature of the filmmaker's pain, which he names in this passage, is not explicit in his film diaries; perhaps it cannot be, perhaps insofar as it preceded his acquisition of a camera, or perhaps he cannot bear to speak of it.

[…]

Throughout his career Mekas has been careful to accumulate images of himself. Repeatedly, he put the camera on a tripod for a formal portrait. He loads the final minutes of As I Was Moving Ahead… with so many stunning instances of these self-portraits that their frequency announces the imminent closure of the long work. After the last of three appearances of the intertitle “that moment everything came back to me, in fragments –“ he inserts a brief glimpse of Una Abraham at her baptism (the first titled scene of Chapter One) signalling that the span of memory encompasses the whole film. Such gestures indicate a formal reorientation insofar as the filmmaker no longer allows chance to play a dominant role in the sequences of his work. He interrupts the final crescendo with two minutes of meals, birthday parties, and children playing. The passage ends in a frenetic dance in which the filmmaker appears to be getting a ride on his shoulders to a child. It is during this scene that he begins to sing the long concluding chant that begins: “I don't know what life is.”

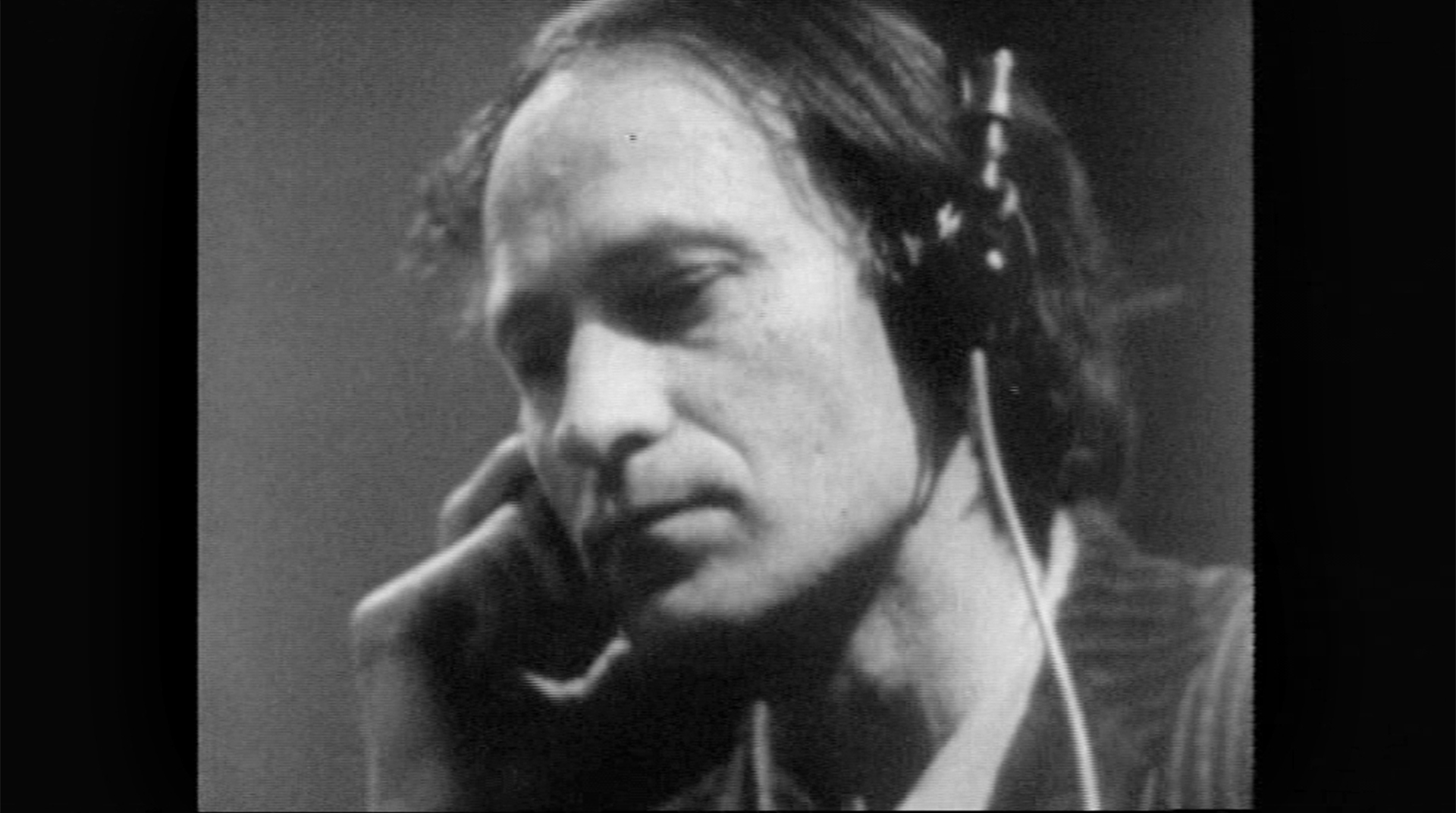

Finally, there is a radiantly happy shot of Hollis kissing Jonas’s cheek as he drinks a glass of wine. It is the culmination of the concluding chapter’s ode to happiness; evidently the filmmaker withheld it for this capstone position. By placing it where he does, he toasts his wife, their years together, and greets his future viewers. For the finale of the film he gives us another self-portrait. He took this one when he was finishing the editing; the 78-year-old poet looks at the camera and figuratively, at us, and back on the images of his life. By making the final image of himself seemingly twenty years older than those we see in most of the film, he dramatized the leap of time between shooting and editing.

Adapted from P. Adams Sitney’s book Eyes Upside Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008, in Jonas Mekas, boxset Potemkine

David E. James, Film Diary / Diary Film: Practise and Product in Jonas Mekas’s Walden, page 157. “The constantly voyaging camera creates a continuous stream of visual aperçus, alighting on one epiphany after another – a face, a cup of coffee, a cactus, a foot, a dog scratching itself, another face, a movie camera.”

Jonas Mekas (1922-2019) was born in the farming village of Semeniškiai, Lithuania. Being a poet and involved in his community already at a young age, he found himself conscripted into forced labour in Germany and then a displaced person, banished to America at age 27, along with his brother Adolfas. Two weeks after his arrival, he borrowed the money to buy his first Bolex 16mm camera and began to record brief moments of his life. Soon he got deeply involved in the American Avant-Garde film movement. In the early 1950s, he made his first documentaries. He founded the movie magazine Film Culture in 1955. Five years later he was involved in the creation of the New American Cinema Group. In 1962, he started the New York Film-makers’ Cooperative. He co-founded and directed the Anthology Film Archives in New York in 1970. He joined the Fluxus movement founded by fellow Lithuanian George Maciunas. Mekas was the sole exhibitor at the 2005 Venice Biennale Lithuanian Pavilion. In his last twenty years, he also published a dozen books with his diaries, poems, dreams, articles, anecdotes, and conversations.

Guns of the Trees (1961), The Brig (1963), Award Presentation to Andy Warhol (1964), Notes on the Circus (1966) Cassis (1966), Diaries, Notes & Sketches (Walden) (1969), Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972), Lost Lost Lost (1975), In Between (1978), Notes for Jerome (1976/1978), Paradise Not Yet Lost (1979), He Stands in a Desert Counting the Seconds of His Life (1988), Scenes from the Life of Andy Warhol (1990), Zefiro Torna or Scenes from the Life of George Maciunas (1992), The Education of Sebastian or Egypt Regained (1992, video), Mob or Angels (1993, video), Imperfect 3-Image Films (1995), On My Way to Fujiyama I Met… (1995), Memories of Frankenstein (1996), Happy Birthday to John (1996), Birth of a Nation (1997), Scenes from Allen’s Last Three Days on Earth as a Spirit (1997, video), Simphony of Joy (1997, video), Song of Avignon (1998), As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty (2000), Notes on an American Film Director at Work (2008), Out-Takes from the Life of a Happy Man (2012)

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE