Focus Milena Gierke

NEW YORK FILM DIARY SEP. 3, 1994 - OCT. 3, 1995 (Germania, 1995, 90’) - Proiezione in Super8.

Alla presenza della regista e dei curatori Federico Rossin e Rinaldo Censi

In 1942, Henri Matisse wrote down a few notes after reading Louis Aragon’s manuscript “Matisse in France” on the drawings of his series “Thèmes et Variations,” “When I execute my drawings for Variations, the path that my pencil follows on the sheet of paper has something in common with the gesture of some man who was looking, blindly, for his way in the dark. I mean, nothing is predicted in my pencil’s track: I am guided, it’s not me who guides.” It is the inner gaze that guides Matisse. Regarding the Thèmes, his reasoning is more blurred: “I haven’t seen yet the way in which I proceed with equal clarity, because it is more complex and more deliberate. This ‘more deliberate’ is a serious obstacle to clearly seeing what really matters – because the ‘more deliberate’ prevents instinct from surfacing in all its evidence.”

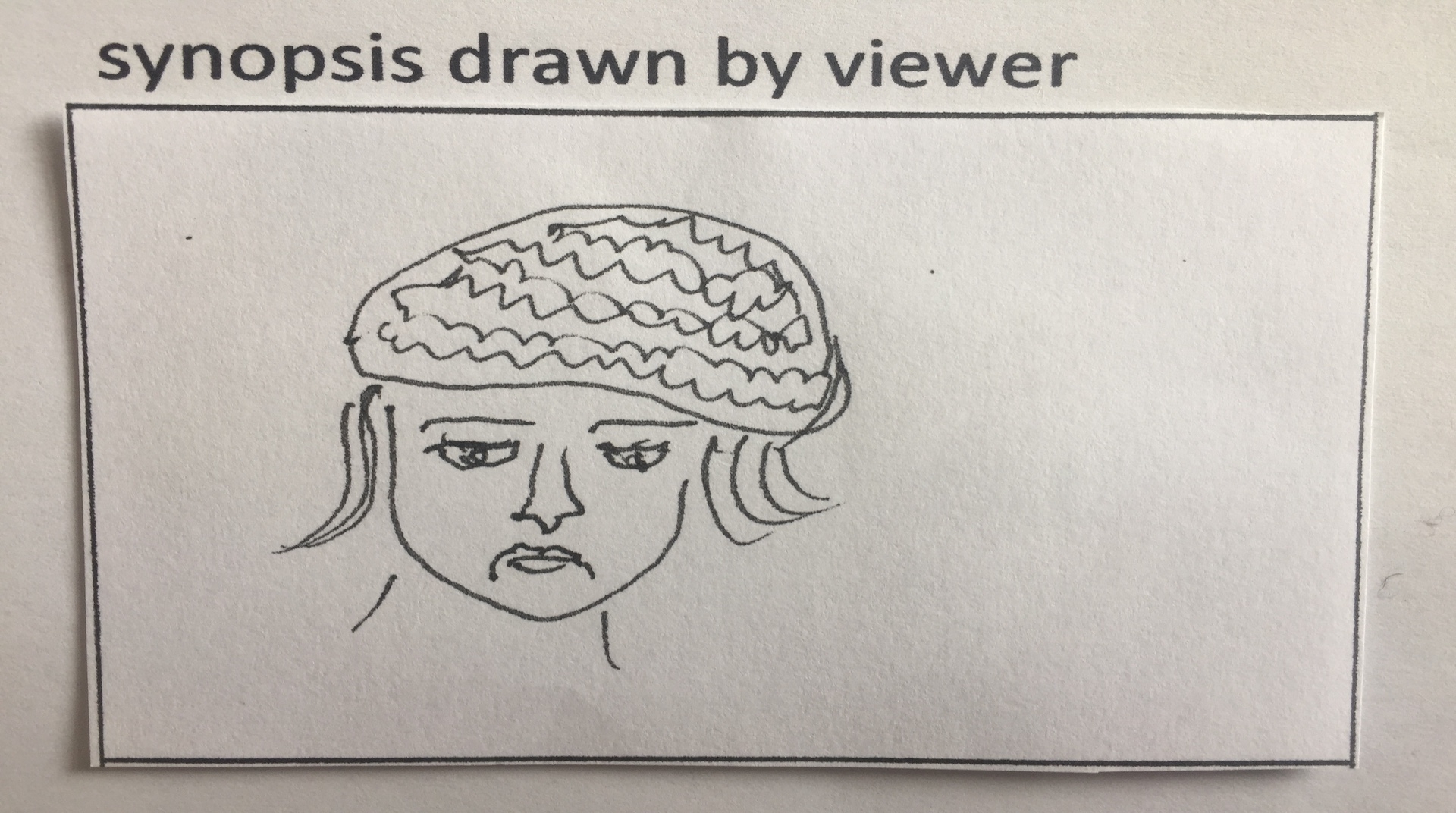

We could say that Milena Gierke’s films lie somewhere in-between these two ends, the inner process and the deliberate gesture, including all the nuances in the interval. Journal-like forms, sketchbooks. The person who creates them is a viewer, an accountant, a fickle archivist of unwritten things captured through observation. The films’ rhythm is given by movements reminiscent of those of a clock, as they are dictated by mechanisms, connecting rods, the Super 8 camera’s cams. The little movie camera becomes a highprecision musical instrument. The frame speed is controlled by Gierke’s finger on the lever. New York’s skyscrapers, the weather, a panoramic view, water, light’s different stages, or a mere frog, resting on the bed of a torrent: each element has its rhythm, its own life, modulated by the camera’s ‘pace.’ The musicality of things. “Musica est scientia bene modulandi,” according to Augustine in De musica (“Music is the science of modulating well”). Thus, “it is well modulated whatever is moved according to numerical ratios that abide by the measures of times and lengths.” Milena Gierke modulates well.

Credit photo: Martin Schoeller

Milena Gierke, born in Frankfurt am Main in 1968. 1989-94 studies at the Frankfurt Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Städelschule, in Peter Kubelka’s class “Film + Kochen” (film & cooking). In 1994, she studied sculpture at the Cooper Union in New York City with Hans Haacke and film history with James Hoberman. Other faculty were representatives of the US film avantgarde, such as Ken Jacobs or Robert Breer. In 1995 Jonas Mekas, who has greatly inspired Gierke for her diary films, screened a three-hour retrospective of her work at Anthology Film Archive. Since 2001, she has been a member of the curatorial group “Filmsamstag” at the Filmkunsthaus Babylon, Berlin. The artist lives in Berlin since 1998.

Interview a Milena Gierke

Federico Rossin

What prompted you to become a filmmaker?

I am an open and curious person. Many arts appealed to me and I couldn’t choose just one direction. A bit of writing, drawing and painting, playing the piano, dancing. My father has always written, my mother painted, all that was familiar to me. After graduating from high school, I lived in Paris for a few months with my cousin, who is a film actress and was shooting a lot at the time. And sometimes I visited her on the film set and watched her working. At some point it clicked with me, and I realized: “I want to make films, too. But not feature films like the ones I saw during the shoot. I want to make films without actors nor crew nor script. I never want to have the camera taken out of my hands, but to decide and execute everything on my own. I don’t want anyone to play anything for me, to pretend. I want it all to be real.” Maybe it was a feeling like the Impressionists had when they decided you had to get out to paint nature on location.But I didn’t know any experimental films at that time, or any films at all, except some feature films and conventional documentaries. Through a small film club I got a video camera and made a small film about «self-portraits in art». With that I applied to the Städelschule (the art academy in Frankfurt). And only then, when I ended up with Peter Kubelka during my art studies, did I know: this is exactly the right place for me! And then I also knew that with the medium of film I could always include all the other arts that interested me, if I wanted to. With this certainty, I was able to commit myself completely to the medium of film.

Since from your first film, you have adopted a diary film form: why have you chosen this style of making films, which mixes life and cinema all the time?

It has to do with the fact that I probably came to film more from art. I read diaries and wrote some myself. The paintings and drawings of artists who focused on everyday life have always interested me much more than any biblical or narrative situations. The painters who, in search of themselves, always looked critically at themselves in the mirror and regularly painted self-portraits such as Rembrandt, Dürer, van Gogh, Munch, and Paula Modersohn-Becker have fascinated me very much. For example, van Gogh and Modersohn-Becker also painted simple everyday situations. When I found these observations in early films such as Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera or later in the diary films of Mekas, or in the multifaceted observations of Brakhage, I knew that film was the artistic form for me. The constant comparison of similar situations and their changes in detail. The joy of observing and noticing these small processes: for example, how an incidence of light changes. Or how something useless in the sunlight and a special perspective becomes something beautiful. You can actually find this everywhere, if you open your eyes and you can already enjoy something and be grateful to recognize this and be allowed to experience it. It is a kind of ode to life. And I would like to share my kind of gratitude to life with my films with other people.

You have always worked with a Super 8mm camera: why have you adopted this peculiar amateur technique, and how did this light camera influence your work?

When I joined Peter Kubelka’s film class, video was in its very early stages and most students were using 16mm cameras. I was fascinated by what they were doing with the camera and also tried my hand at the 16mm format, but I had great difficulty operating the light meter. Technology, numbers, and abstractions have always been near incomprehensible to me, but only recently I understood why: I have dyscalculia. Anyway, the advantage of an integrated and automatic light meter, as well as the small and light camera that still uses real film, convinced me to try Super 8. Especially with the camera editing, it lost any stigma (of not so clean film editing). So sometimes it is good to go along with your difficulties and find an interesting solution! Later, I would love to show my S8 films (almost all without sound) to an audience, and to make a kind of performance out of the screening. In addition, the rattling of the projector that is similar to a heartbeat is a sound that goes with it. The most important thing has always been the combination of the quality of analogue film, which is the same in Super 8 as in 35mm, and the possibility of super-precise camera editing during the filming process. This is made possible by the manual operation of the non-electronic camera. In a fraction of a second, I’m filming and I release my finger from the lever and «stop» - I’m not filming anymore. Precise as with a musical instrument. And finally, this small, light camera is equipped with the integrated light meter, which I could always operate nimbly and quietly without a tripod. So, my little Super 8 Bauer camera became like an extended arm with eyes to me.

How much is the editing process important for you? and the spontaneity in shooting?

In connection with film editing, this is probably the most important point in my cinematic work: camera editing. Technically, it means that after the filming process, you don’t change the film. While in most feature film and documentaries the creative process really takes place after the shot scenes have been developed, my films are ‘cut in the camera’ and thus already finished. Accordingly, the only work, and the most important work of all, is to get everything right during filming. Everything that is filmed will be seen in exactly that way in the film. So, camera editing means: avoiding mistakes wherever possible, making decisions immediately and having to live with everything you’ve shot the way it turned out. Just like in real life, where you can’t turn back a day... So: max concentration when shooting! It’s similar to watercolour, where every brush stroke remains visible, unlike oil painting where you can paint over and over again. Or like a free-jazz concert, where the composition is created as you play. In principle, of course, camera cut renounces many possibilities of film: namely, to change the chronology and order of events at will. But that’s just the difference between a scripted procedure and an intentional, ‘planned’ snapshot. For many people, the technique of this art form, ‘camera editing,’ is difficult to understand, but once they do understand it, they like my films all the more!

Who are the filmmakers and artists that had a major influence on you?

First, I encountered some painters, they influenced me as a child; filmmakers and pho-

tographers only later during my studies. Painters: the old Flemish and Dutch masters, especially Vermeer, then Velasquez, the Impressionists, all the painters mentioned before. Filmmakers: Eisenstein, Vertov, Dovzhenko and Man Ray, Richter, Len Lye, and then especially the later North American avant-garde: Brakhage, Mekas, Kubelka, Breer, Snow, J.J. Murphy, Anger, Deren...

Photographers: Sander, Blossfeldt, Rodchenko, Cartier-Bresson, Stieglitz, Frank, Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, Besnö, Strand, Lange, Weegee, Adams, Capa, Friedlander, Arbus, Modotti, but also newer ones like Anna and Bernhard Blume, Gerald Domenig...

In your films, there’s a musical syntax which makes us think of music: how much did music influence you?

Above all, the insight that everything that is artistically processed within time also has a rhythmic component. When you move a flip book, you immediately feel how musical images can be even without sound. This is what silent films, but also films of the avantgarde, have taught me. Rhythm is like day and night or the heartbeat, and thus very close to real life. Time contains rhythm and you can compose with it even without sound. So, it was not the music that influenced me directly. Only the theoretical knowledge of how to use time and rhythm to build tension or emphasize things, for example.

An important part of your work is about architecture: how do you ‘read’ a building? Which role plays intuition in this work? Do you explore the architectures before filming them, or not?

I fall in love with a building. I feel it mostly physically: I get all excited when it happens, and all my attention just goes to the building. I want to see it from all sides and walk around it, taking in every perspective, capturing its beauty. A film about a building is a kind of love letter in which I let the viewer read along. Yes, in my enthusiasm I want to shout out to everyone how beautiful this building is: everyone should know and be able to comprehend it! That’s the intuition. So, I also read it with my whole body. Of course, the visual experience comes first in the foreground. Especially the play of light, at different times of the day and year. How does

it relate to the outside world? Through what kind of windows? Then usually comes the acoustics, the reverberation of sound in a church or a large building, how do my footsteps and those of others sound? What does it sound like when people speak or sing? And then, most importantly, comes the sense of touch, or rather my total body movement relating to the building: do I look very high or down, towards things close or in the distance? How does it feel when I’m in the basement? What is the texture of the material? For example,the handrail. Most of the time, I know very quickly whether I’m falling in love or not. And if this is the case, my artistic perception process begins immediately. Whether I then film it immediately or later varies, depending on time and possibilities.

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE