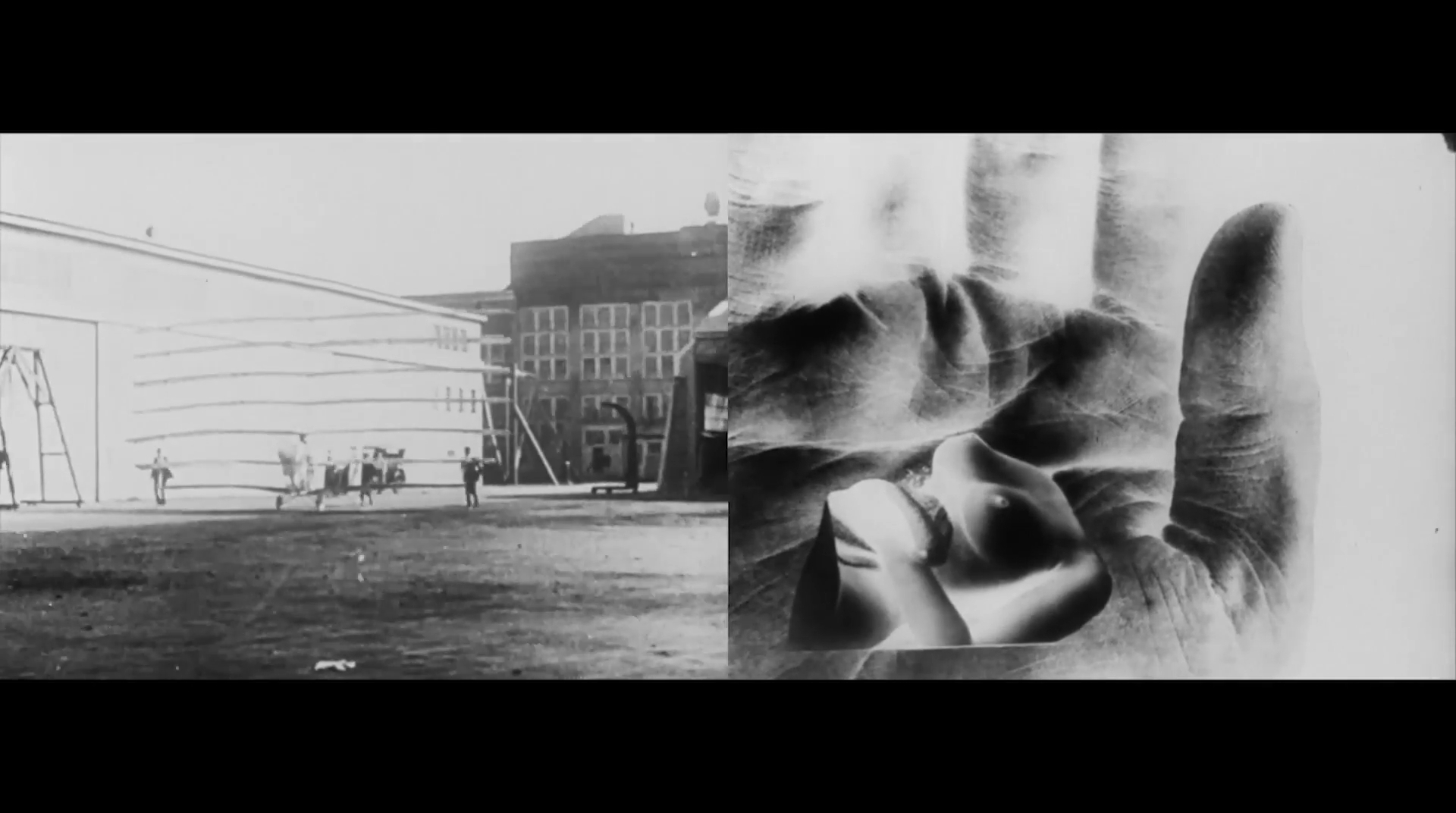

Stan VanDerBeek - A Dam Rib Bed (1964-1965)

film in 16mm su doppio schermo, 15’

“A two screen Dream/Film/Farce/Sity about sleeps-two-sides-the Dream-Beast, animated trick photography combined into a knifed dream with a sexual dreams edge. A movie mural, based on the gender question. In question or sexus plexus... Dayglow dream life... Slides films.” (Stan VanDerBeek) VanDerBeek's ironic compositions were created very much in the spirit of the surreal and dadaist collages of Max Ernst, but with a wild, rough informality more akin to the expressionism of the Beat Generation. In the 1960s, VanDerBeek began working with the likes of Claes Oldenburg and Allan Kaprow, as well as representatives of modern dance, such as Merce Cunningham and Yvonne Rainer. Building his Movie Drome theater at Stony Brook, New York, at just about the same time, he designed shows using multiple projectors. The Movie Drome was a grain silo dome which he turned into his ‘infinite projection screen’.

Stan VanDerBeek (1927-1984) was a prolific multimedia artist known for his pioneering work in experimental film and art and technology. His filmography includes over one hundred experimental and innovative 16mm and 35mm films and videos in black and white and color spanning collage, animation, computer graphics, live action, performance documentation, found footage, and newsreels.

EXPANDING VISION – MULTI-SCREEN FILMS OF THE SIXTIES AND SEVENTIES

a programme curated by Federico Rossin

For Adriano Aprà

Multi-screen films are a unique cinematic experience, enveloping the audience in both spatial and sensory terms. In this immersive film experience, which rejects the single-screen synthesis and moves towards the open work, the third dimension of real space is incorporated into the staging of the event, dissolving the boundary between the architectural ‘room’ and the spaces of virtual projection to establish a poetic space of mixed reality.

From the late 1950s, multi-screen projection broke forth in the pavilions of international fairs worldwide: suffice it to mention Roman Kroitor, Alexander Hammid, Francis Thompson, just a few of the great filmmakers who tested their experimental research and practice with the general public. The works of Nam June Paik, Aldo Tambellini, and Juan Downey followed closely, creating spectacular events in which they used multiple media, attracting large and diverse crowds composed of artists, connoisseurs, onlookers, and cinephiles. Establishing an actual dialogue between avant-garde film and the other media, these multi-screen events helped experimental traditions and audiences interplay not only between themselves, but also with mainstream technologies and spectators.

Over this sparkling period of experimentation, artists from all disciplines devoted their attention to the material qualities of the screen, to the spaces in which these screens appeared, and the communities that would gather around them. In many cases, the filmmakers themselves would play the roles of programmers, distributors, and projectionists of their experimental films (Kenneth Anger used three synchronous projectors and three screens to show his Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome at the Brussels International Experimental Film Festival in 1958). The experimental screens of the 1960s and 70s, in all their forms, saw the convergence of different media and different milieus for the first time: the art world (e.g., Andy Warhol and his Outer and Inner Space and Chelsea Girls, 1966), the world of avant-garde film (let us not forget Jordan Belson, who was Visual Director of the Vortex concerts at the San Francisco Morrison Planetarium from 1957), and mainstream audiences got together for the first time.

The ‘new vanguard’ filmmakers of the 1950s and 60s were fully conscious they belonged to an old story (Maurice Lemaître’s syncinema, 1952) and therefore tried to rekindle the connections with the 1920s avant-garde artists, those who first had theorized multi-screen ‘expanded’ cinema – initially in very imaginative books (László Moholy-Nagy’s polycinema, Dynamik der Großstadt, 1921-22) and then practised in live performances (Oskar Fischinger, Raumlichtkunst, 1926) or spectacular films (Abel Gance’s polyvision: Napoléon, 1927).

Dominique Noguez found the origins of this screen multiplication in cinema in a series of closely linked desires: the desire to extend the screen; the desire to create immersive spaces, integrating cinema with other recorded media; the desire to use cinema performatively, coming into direct contact with the audience; and the desire to explore the film process – the deconstruction of the elements of cinema in which the work becomes the elements themselves.

The experimental film production of the 1960s and 70s expanded not only the notion of screen, but also that of the whereabouts in which screens could be placed and used. Gene Youngblood, in his pioneering book Expanded Cinema (1970), documented this multiplication of screens citing experiments with vans used as mobile cinemas, portable inflatable screens and projections in artists' spaces and galleries, in public and private television stations, on concert stages in combination with live music, in planetariums, in private homes, in university classrooms, in churches and clubs, and in huge multi-screen locations, which used multiple media simultaneously such as projections in different film formats (IMAX, 35mm, 16mm, and 8mm), slide projectors, and TV monitors. Immersive cinema ranged from the concept of ‘expanded cinema’ introduced by the counterculture movement of the 1960s to the multi-projection video art installations of the 1970s, from unframed hemispherical projections to the cinematic collage of assorted projections, originally projected in the dome of a planetarium made by Stan VanDerBeek in his Movie-Drome from 1965 onwards: the aim was always to facilitate a certain ‘mental mutation’ in the audience.

The select, but significant two- or three-screen film projections that we propose were conceived to be dazzling audiovisual events and aspired to deeply engage the audience. Having two or more images projected makes it possible to analyse, play with, or create all sorts of new synoptic possibilities for the artist and the audience. The relationships between shots and images can be explored not only sequentially, i.e., one after the other in time, but also simultaneously and through the physical space of the film screen. The immersive and hypnotic qualities of light, image, editing, and double projection – and their psychological impact on the individual – are explored with extraordinary effects that multiply the possibilities of expanding consciousness and analysing the film machine. A synesthetic universe in which we want to plunge into again, body and soul!

Federico Rossin

ALL SCREENING ARE FREE