Allegoria della luce e dell’ombra

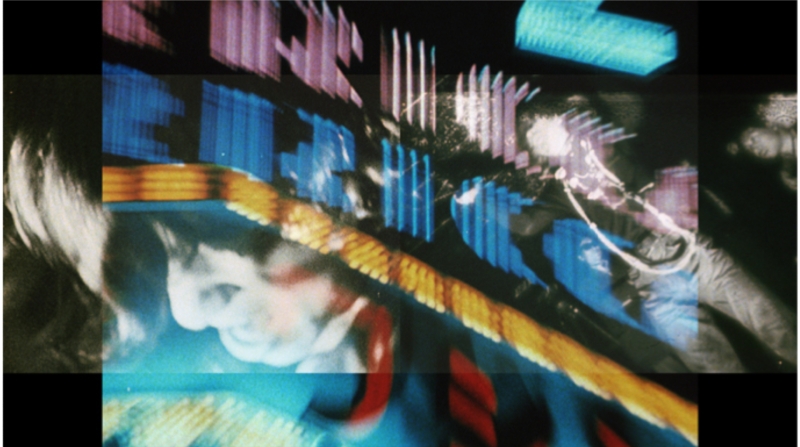

Italia, 2009, Super 8, colore, muto, 18’

Regia, soggetto, fotografia, montaggio, disegni e fotogrammi dipinti: Arcangelo Mazzoleni Interprete: Mariella Buscemi

A journey into light and colour throughout the layered archetypal memories belonging to the Sicel-Greek world, mixed with personal, autobiographical memories and places, and reexperienced through the filter of Myth.

With the presence of the curator and the director

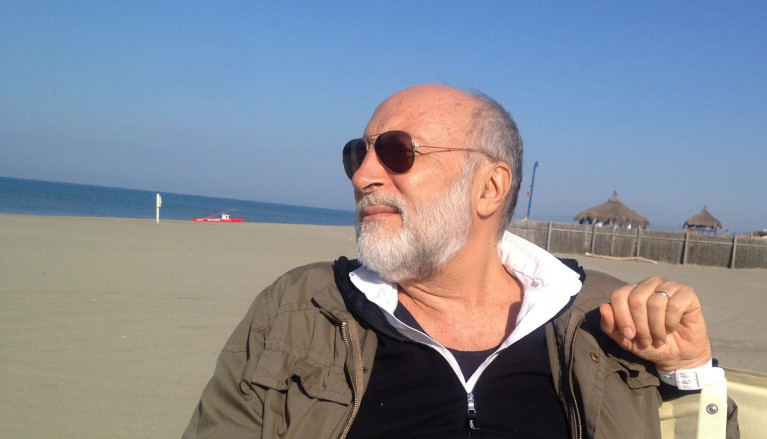

Arcangelo Mazzoleni (Catania, 1953) is a visual artist, film director, poet, essayist, playwright, critic, theorist and university lecturer in film. A graduate in Humanities from the Sapienza University in Rome, since graduating from the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia he has developed an integrated expressive project through a multiplicity of linguistic forms: from poetry to cinema, from experimental theatre to visual arts (painting and photography), from aesthetic theory to criticism. Over the years, he has taken part with his films in festivals and collective exhibitions in Italian and foreign institutions, including: Audiovisuelles Zentrum (Graz); Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris); Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Maxxi (Rome); Curzon Soho Cinema (London, 2003); Fondazione Guggenheim (Venice); BizArt Centre (Shanghai); Film-Maker's Coop (New York). His solo exhibitions include Arcangelo Mazzoleni: il mondo al fuoco dello sguardo. Film, video, disegni, tecniche miste su carta, Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica in Rome (1994); Incontro con il cinema di Arcangelo Mazzoleni, Filmstudio (Rome, 1986); Incontro con Arcangelo Mazzoleni, artista fotografo e regista, Museo dell’Immagine Fotografica e delle Arti Visuali of Rome University Tor Vergata (1996); Incontro con Arcangelo Mazzoleni: lectio magistralis and screening of his films, Faculty of Education Sciences (University of Padua, 2003); Corpi e mondi in vertigine: film e poemi di Arcangelo Mazzoleni. Anni Settanta/Ottanta, Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea (Rome, 2018).

My Uncanny Cinema

A talk with Arcangelo Mazzoleni

What is the reason why you have constantly used the Super8 for your experimental films, in spite of your professional background?

At the Centro Sperimentale I would work with the 35mm format or the 16mm Arriflex. However, I had already discovered the versatile Super8 film cameras, like the Beaulieu, which allowed rewinding the film strip inside the camera and making cross dissolves and multiple superimpositions, as well as filming frame by frame in animation or filming moving bodies with the pixillation technique. Moreover, their light weight would facilitate handheld shooting and travelling shots. With this approach, it was like going back to the creative, magic and primitive, childhood of cinema, not to mention that it contributed to a symbiotic relationship between myself and the camera, which would become an extension of my body, a ‘hyper-eye’ open onto the world.

Why have you made so few films over 35 years?

I have never felt the need of producing more films, as I aim to the quality of the research and the discoveries it entails, as well as the new languages that can be developed. I compose ‘visual scores’ in which clusters of frames alternate, contrast, reiterate through the technique of variation, coming back in ever new associations. This work of ‘composition,’ then, resembles that of the musician working with Time. It requires concentration and an inner commitment to a project that is often there, but only as an ‘inner music,’ waiting for taking shape in images. The latter are organized following the rhythm of a metrics, based on pauses, resumptions, accelerations, and variations.

What is your cultural point of departure, and what the unifying factor in your cinema?

Surely, having been surrounded by the attention of a myriad of women (grandmothers, aunts, aunts’ female friends, governesses) influenced my vision, that points to the narrative of the Feminine. Moreover, my cinema is also a cinema of places that are internalized and become spaces of the soul. Childhood places, daily, habitual, familiar ones, those that – according to Freud’s principle of the unheimlich – suddenly turn out as uncanny. On top of this, having grown up in the sixties-seventies meant I experienced the years of the protests ideologically, which helped me conceive art as an instrument of demystification and alteration of reality – see the staging of Diktat, Il Tempo del Titano, a multi-media show in which, following Svoboda’s steps, I would use film to experiment with the integration of physical bodies on stage and the immaterial, visionary images of the projections.

For me it’s difficult to separate your cinematic and photographic imaginary, since you make them interplay perfectly, joining them by way of a sensitivity strongly influenced by painting.

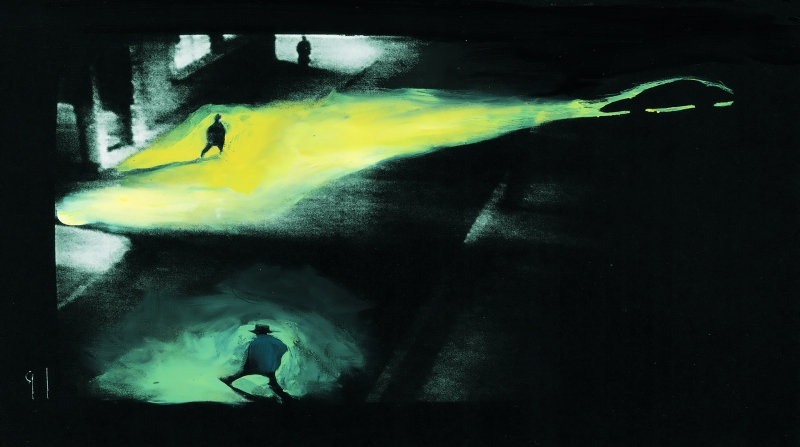

In fact, I feel there is a powerful complementarity between the two languages. Exploring the potential of photographic language (in particular with studies of the body and how it interacts with colour; its dislocation on different spatial planes…) gave new lifeblood to my research in film, which fuelled on the chromatic and figurative ‘discoveries’ and experiments conducted in photography. Film drove me towards ‘gigantism’ of photographic images: the large Cibachrome polyptychs made for the 1994 exhibition at the Calcografia nazionale would extend over the entire walls while the screens projected the same images made dynamic and developing over time. One more level was constituted by the numerous drawings and storyboards that showed the inception, the early insights of this research: the idea captured on paper for the first time and ready to become image, whether static or developed over Time.

In your films, there are references spanning from the historical avant-garde to underground cinema, especially north American. Who are the other experimental filmmakers that influenced your work?

When I was at the CSC, I had the chance of meeting Kubelka, a CSC alum, who during his visit screened his films. His idea of metric cinema met halfway my vision of film as a stream of consciousness, a Joycean interior monologue where the quest for the Other is dominant. Other reference directors are Brakhage, Anger, and Carmelo Bene, for the use of colour, but also Pasolini and his ‘cinema of poetry’, Godard, or the Jodorowsky of El Topo and The Holy Mountain.

Are you currently working on some new film?

I am thinking about a film in 35mm format that incorporates Super8 footage; the 35mm pictures represent the plane of reality, whereas those in Super8 the infinite inner space. I also have an exhibition project, partly to follow up and recontextualize the research done so far and partly to propose new suites of images, blown-up film frames conceived as individual art works. And then I intend to publish an autofiction in which I describe the years of my formation as an artist – a journey through memory bound to the fairytale lands of childhood and youth, which is also a voyage through the “heart of darkness” of the 20th century. A portion of the autofiction’s narrative passages should be recorded and become part of the exhibition as acoustic installations, in dialogue with the photographic images, the films, and the texts on display. In short, for me the work of research is like a huge potential repertory of images, myths, and expanding narrative universes capable of contrasting the standardized imaginary of the globalized world.

Arcangelo Mazzoleni

The Texture of the Subconscious

Bruno Di Marino

A philosophical-literary influence can certainly be found in the cinema of Arcangelo Mazzoleni (spanning from de Nerval to Rimbaud, from Goll to Blake, from Freud to Merleau-Ponty), not to mention an important and inescapable reference to the historical avant-garde season and to the iconographic culture of Surrealism. But what strikes most when watching and rewatching his short films – made over three decades (1978-2009) – is Mazzoleni’s capacity to conduct a fascinating and articulate exploration of our states of mind and their layering. Not coincidentally, one of his earlier films is entitled precisely Lo spazio interiore, thus emphasizing how this space – which is invisible and yet takes shape through clues, fragments, engrams, and flashings – is habitable and passable in almost physical terms.

The visionary, psychedelic, and in many occurrences totally abstract cinema of Mazzoleni is like a journey inside the innermost subconscious, from which it extrapolates images that recur obsessively, transmigrating from a film to the next, accompanied, in some instances, by a minimalist acoustic texture that underscores its serial structure even more. On the other hand, the binomial frequencies/sequences evoked in the title of another work (Composizione per sequenze e frequenze, 1978) point indeed to both musical and cinematic composition. “Rhythm is akin to music, therefore taking photographs or shooting films for me is the same as creating visual scores,” wrote Mazzoleni.

The format chosen throughout this research, that has always been conducted on the ground of both photographic and moving image, is certainly not secondary. The Super8, in fact, is a difficult, ‘poor,’ low-definition medium. However, thanks to the ability of the artist from Catania (but a Roman by adoption) and his capacity to mould and transform this format, it becomes a ‘noble’ matter with an enviable level of perfection, elegance, and resolution. The artist’s will to alchemical transmutation also manifests itself, according to the same Mazzoleni, in transferring onto the language of film and photography the rhetorical and expressive tropes of poetry, i.e., metaphors, synecdoche, similes, climax and anticlimax, iterations, and amplifications.

Finding echoes of the present in Mazzoleni’s imaginary seems difficult, because his cinema appears to be comprised between mythical, ancestral past and fleeting mnesic traces. And yet, if we depart from one of his most figurative, even narrative, films, Le Temps des assassins (1986), we are tempted to read – besides the reference to the cult of Hashishins, who would commit murders under the influence of substances – an allusion to armed fight: the woman driving with a gun on the dashboard, the bikers, men exercising at the firing range (videotaped: footage ‘stolen’ from monitors is recurring in the cinema of the artist) are all elements of ‘reality’ or of a pseudo-diegetic plot within which electric interferences keep on bursting. The result is a dimension poised between classicism (the columns of a temple) and modernity (the TV antennae), civilization and nature.

Fragments of a possible narrative are also found in Aurélia and Anabasi (made between 1979 and 1981), such as a recurring image – a trope of thriller-horror film – with the point-of-view shot of someone about to operate a handle and open the door. A stereotype we had already seen in Lo spazio interiore, but becoming more explicit in Aurélia, juxtaposed with a knife and even a doll’s head hanging, besides the shadow of a bird whose fragmentary and confused flight (another theme also present in Lo spazio interiore) we have been following in the opening scene. Suddenly, an insert of an entirely different kind: footage of Julian Beck and Living Theatre filmed during a performance. Instead, Anabasi opens on a quote from Freud – “Thought is only the surrogate of hallucinatory desire” – which leaves little doubt to the fact that the visions on which Mazzoleni constructs this and other films are freewheeling associations/obsessions which are placed in different positions within the chain of events depending on the situation. The dream is evoked showing a woman in a waking state, while by way of dissolves (obtained via multiple exposures) abstract images come to the surface, with veils, fabrics, jewels, bracelets, shiny filaments. Slow-paced images in which symbolic-ritual objects, standing against red, green, and blue, once we have gone through the same door seen in Aurélia leave room to an atmosphere reminiscent of a horror movie: a fruit cut by the knife, a face of a screaming woman, and an insert with Mazzoleni filming his own face in extreme close-up while he runs in the countryside.

A film of the maturity, in which a series of themes and suggestions converge, taking Mazzoleni’s poetics and aesthetics to the highest levels, is Da corpo a cosmo. Conceived for his solo exhibition at Calcografia nazionale in Rome, the film generates a series of large Cibachrome pictures. The short features two techniques: time lapse, with which Mazzoleni films the cloudy sky looming over Catania, dominated by snow-covered Etna; and optical print compositions, that create a dialectic between static/moving images, transforming these colourful visions/scans in abstractions somehow reminiscent of the works of early Futurism, Balla, Carrà, Boccioni. All is cemented by the minimalist music that marks rhythmically the masks, faces, bodies, leaves, trees, church glass windows, and light refractions in interiors following one another. Also for the exhibition, he made Il mondo al fuoco dello sguardo and the next film, Mandala Opus #7, which incorporates some sequences from Da corpo a cosmo and other images too – like the recurring eye (a hint to one of the key symbols of historical avant-garde cinema) – and continue the discourse on the relationship man-nature-cosmos.

Twenty years on, the artist has gone back to film experiments with Sole nero, whose deeply alchemic meaning at times reminds us of Brakhage’s hand-painting onto celluloid, and even more with Allegoria della luce e dell’ombra, a short that perfects the use of optical print creating fine abstractions from sculptures, including a skull (a reference to the vanitas iconography), and following up on the mandala theme found at the core of the previous film. Blake’s epigraph placed at the film’s ending, “'If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite,” seals this umpteenth, last – at least so far – journey in the world of interior images that Mazzoleni has performed, trying to gift us with the texture of the subconscious in all its infinite beauty.

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE