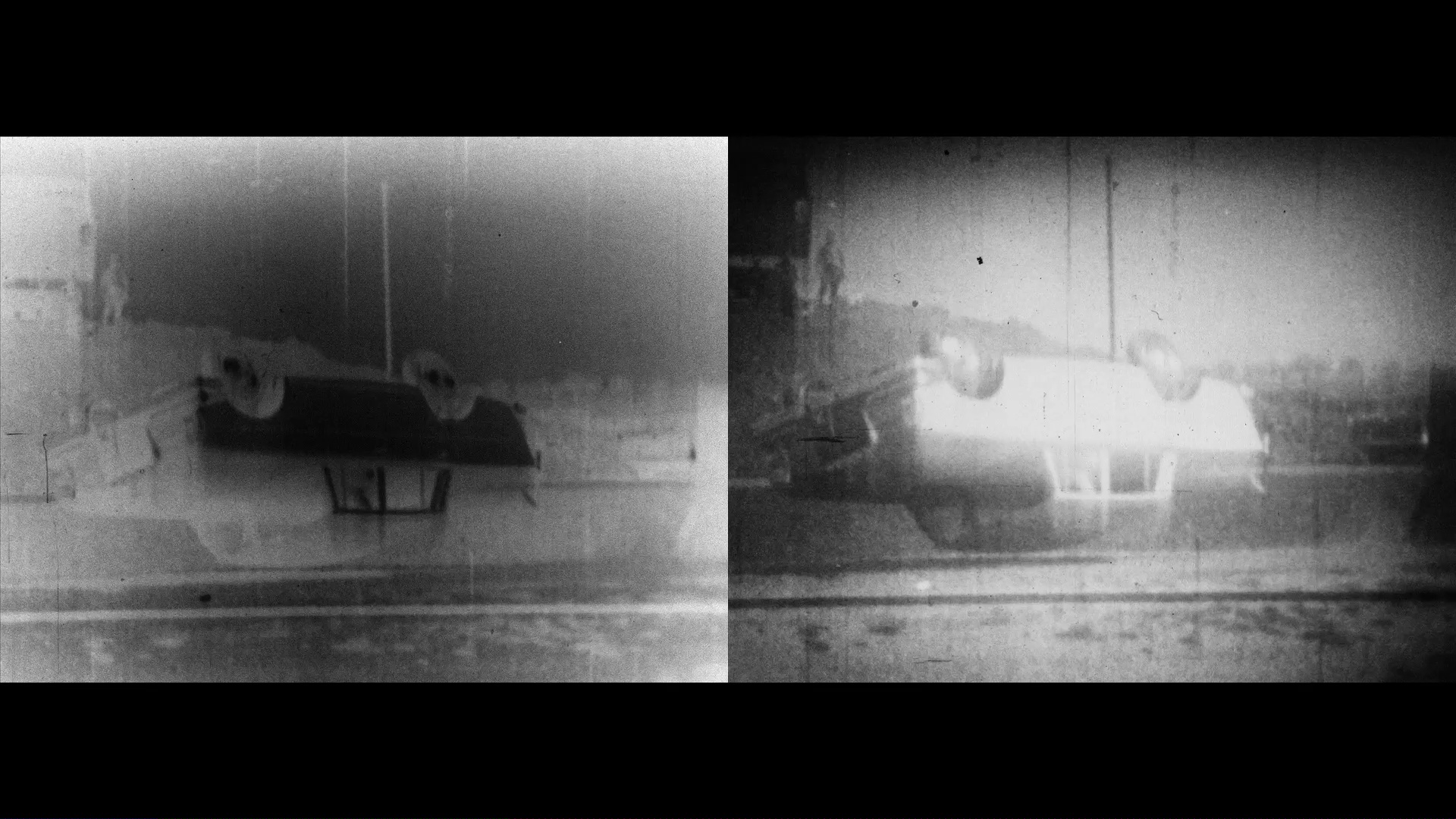

David Parsons - Mechanical Ballet (1975)

film in 16mm su doppio schermo digitalizzato su video monocanale, 9’

“The original material that formed the basis for Mechanical Ballet was an anonymous short reel of film of what appeared to be car crash tests. In the original these tests are carried out in a deadpan and somewhat cumbersome manner. Reworked into a two-screen film and divorced from their original context they take on both a sinister and humorous quality. Using similar techniques to the aforementioned films, the repetitive re-filming of the original footage in short sections emphasized the process of film projection. Somewhat like a child’s game of two steps forward and one back, the viewer is made aware of the staggered progress of the film through the gate. In sharp contrast to the almost stroboscopic flicker of the rapid movement of the frames that alternate in small increments of light and dark exposures, the image takes on new meanings; the distorted reality of two heavy objects (the cars, one on each of the screens) ‘dancing’ lightly in space.” (David Parsons)

David Parsons (1944-2020) was an award-winning multimedia artist and teacher, whose work was exhibited and collected internationally. His palette was broad and innovative, adding photography and film in the 1970s and 80s, and computer-based art in the 90s, to the fine art and painting he had studied in the 60s. He won Arts Council awards across four decades.

EXPANDING VISION – MULTI-SCREEN FILMS OF THE SIXTIES AND SEVENTIES

a programme curated by Federico Rossin

For Adriano Aprà

Multi-screen films are a unique cinematic experience, enveloping the audience in both spatial and sensory terms. In this immersive film experience, which rejects the single-screen synthesis and moves towards the open work, the third dimension of real space is incorporated into the staging of the event, dissolving the boundary between the architectural ‘room’ and the spaces of virtual projection to establish a poetic space of mixed reality.

From the late 1950s, multi-screen projection broke forth in the pavilions of international fairs worldwide: suffice it to mention Roman Kroitor, Alexander Hammid, Francis Thompson, just a few of the great filmmakers who tested their experimental research and practice with the general public. The works of Nam June Paik, Aldo Tambellini, and Juan Downey followed closely, creating spectacular events in which they used multiple media, attracting large and diverse crowds composed of artists, connoisseurs, onlookers, and cinephiles. Establishing an actual dialogue between avant-garde film and the other media, these multi-screen events helped experimental traditions and audiences interplay not only between themselves, but also with mainstream technologies and spectators.

Over this sparkling period of experimentation, artists from all disciplines devoted their attention to the material qualities of the screen, to the spaces in which these screens appeared, and the communities that would gather around them. In many cases, the filmmakers themselves would play the roles of programmers, distributors, and projectionists of their experimental films (Kenneth Anger used three synchronous projectors and three screens to show his Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome at the Brussels International Experimental Film Festival in 1958). The experimental screens of the 1960s and 70s, in all their forms, saw the convergence of different media and different milieus for the first time: the art world (e.g., Andy Warhol and his Outer and Inner Space and Chelsea Girls, 1966), the world of avant-garde film (let us not forget Jordan Belson, who was Visual Director of the Vortex concerts at the San Francisco Morrison Planetarium from 1957), and mainstream audiences got together for the first time.

The ‘new vanguard’ filmmakers of the 1950s and 60s were fully conscious they belonged to an old story (Maurice Lemaître’s syncinema, 1952) and therefore tried to rekindle the connections with the 1920s avant-garde artists, those who first had theorized multi-screen ‘expanded’ cinema – initially in very imaginative books (László Moholy-Nagy’s polycinema, Dynamik der Großstadt, 1921-22) and then practised in live performances (Oskar Fischinger, Raumlichtkunst, 1926) or spectacular films (Abel Gance’s polyvision: Napoléon, 1927).

Dominique Noguez found the origins of this screen multiplication in cinema in a series of closely linked desires: the desire to extend the screen; the desire to create immersive spaces, integrating cinema with other recorded media; the desire to use cinema performatively, coming into direct contact with the audience; and the desire to explore the film process – the deconstruction of the elements of cinema in which the work becomes the elements themselves.

The experimental film production of the 1960s and 70s expanded not only the notion of screen, but also that of the whereabouts in which screens could be placed and used. Gene Youngblood, in his pioneering book Expanded Cinema (1970), documented this multiplication of screens citing experiments with vans used as mobile cinemas, portable inflatable screens and projections in artists' spaces and galleries, in public and private television stations, on concert stages in combination with live music, in planetariums, in private homes, in university classrooms, in churches and clubs, and in huge multi-screen locations, which used multiple media simultaneously such as projections in different film formats (IMAX, 35mm, 16mm, and 8mm), slide projectors, and TV monitors. Immersive cinema ranged from the concept of ‘expanded cinema’ introduced by the counterculture movement of the 1960s to the multi-projection video art installations of the 1970s, from unframed hemispherical projections to the cinematic collage of assorted projections, originally projected in the dome of a planetarium made by Stan VanDerBeek in his Movie-Drome from 1965 onwards: the aim was always to facilitate a certain ‘mental mutation’ in the audience.

The select, but significant two- or three-screen film projections that we propose were conceived to be dazzling audiovisual events and aspired to deeply engage the audience. Having two or more images projected makes it possible to analyse, play with, or create all sorts of new synoptic possibilities for the artist and the audience. The relationships between shots and images can be explored not only sequentially, i.e., one after the other in time, but also simultaneously and through the physical space of the film screen. The immersive and hypnotic qualities of light, image, editing, and double projection – and their psychological impact on the individual – are explored with extraordinary effects that multiply the possibilities of expanding consciousness and analysing the film machine. A synesthetic universe in which we want to plunge into again, body and soul!

Federico Rossin

ALL SCREENING ARE FREE