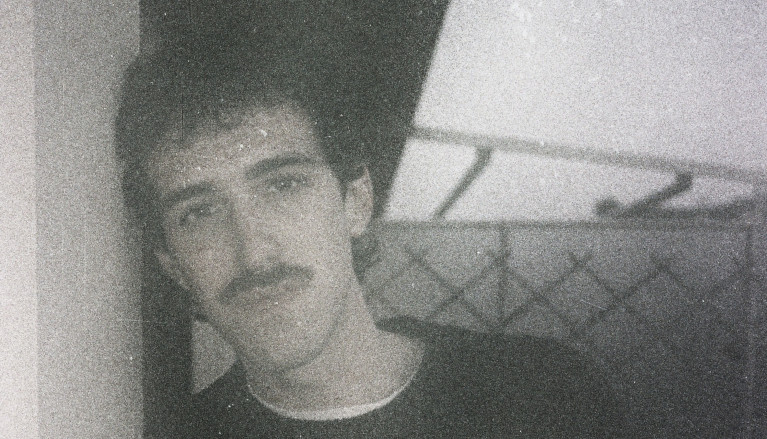

FOCUS: ENEA COLOMBI

Nuova Registrazione 527 (Mara Sattei) 2020

2’28’’

Mentre nessuno guarda (Mecna) 2020

8’03’’

Fette biscottate (Fanoya) 2020

3’48’’

Soli (Mecna, Ghemon, Ginevra) 2021

3’38’’

E te veng’ a piglià (Liberato) 2021

3’56’’

Carlito’s Way (Tropico) 2021

3’45’’

Geniale/ Non esiste amore a Napoli (Tropico) 2021

8’06’’

Ovunque sarai (Irama) 2022

3’20’’

Mare di guai (Ariete) 2023

3’ 22’’

Un milione di notti (Mr. Rain, Clara) 2023 director’s cut

2’’40’’

Durata complessiva 43’ 06’’

Enea Colombi is an emerging Italian film director, born in the Po Valley province, far from the city chaos. A rising talent in Italy and internationally, he started his career at the age of 16, making his first music videos for the Italian rap scene. He now works for international brands and major national artists. Most recently, he won a UK Music Video Award for the video Mare di Guai by Italian pop artist Ariete, becoming the first director to receive this award on a national level. He has received awards and nominations in major industry festivals and online events, such as YDA (Cannes), 1.4, Director's library, Director's notes, Vimeo Staff Pick, Shots Awards, YoungGuns (NY) and Berlin Music Video Awards. The natural environment and the symbiotic relationship between human relationships and nature influence Enea's work and style, generating a narrative world based on a certain magic realism. Art, fashion, and film have always been the three pillars of his work, which he weaves into his commercial, music video, and narrative projects. He recently completed his first short fiction project, a dark fable set on the banks of the Po River. He has debuted in film with the short Il giorno dopo.

by Luca Pacilio

How did you begin working and how have you managed, in just a few years, to make so many videos, and with top-ranking artists?

I was born in a small town in the province of Piacenza in which there is nothing – and if you don’t come up with something, you’re bound to die of boredom – into a family who brought me up between art exhibitions and museums. When I was 14, I already made experiments with a video camera found at home. I had the ambition to go pro, so I began going to local clubs and discos which hosted renowned rappers and DJs: the music showbiz intrigued me, as it was a world concealed backstage which I could watch from a privileged vantage point. At 16 years of age, I began to make contact with record labels of the Turin and Milan scenes. I would propose myself as video maker for free, even though I was ignorant of music video practices. This until the first important opportunity came up, i.e., Mondo Marcio, a music artist who had had an important impact on my adolescence. From then on, it was like a waterfall, and I began to collaborate with artists such as Vegas Jones, Mr. Rain, Elodie, Lazza, and Ernia… I belong to the generation that enjoyed the YouTube boom, in years in which there were few video makers and word-of-mouth played a crucial role.

You acted as an auteur in video making quite soon. For example: it is difficult not to resort to front angle shooting when you deal with such a declaimed song as Mecna’s Mentre nessuno guarda. Instead, your video goes elsewhere, making Mecna the thread connecting the narrative units.

Among the reasons underlying my job, there is the need to both challenge yourself technically and serve the others in a professional perspective. Working with Mecna was fundamental because he gave me great freedom: we immediately agreed to detach from certain models, playback, stars’ self-celebration. Mentre nessuno guarda is precisely the attempt to create a different storytelling – the idea of picking up so many threads and connecting them was supported by Mecna, who gave me full freedom to choose how to cut and recompose the narrative units. The Borotalco company and the producer Luca Degani also trusted me. Luca was key in my growing up because he not only told me that you can say no, but especially that it is important to do that, at times. This contributed decisively to my artistic growth.

You have always cared for image composition, environmental contexts, especially nature, and how the characters are distributed in space.

This has to do with the photographical imprinting I received since I was a boy: I was taught to reason in images. Also, caring for the almost geometrical distribution of the characters within the natural or architectural contexts can be a way to deal with being always on the move, a frantic, turbulent life: as though I wanted to confer that stability and control which I lack in daily life on images. The propensity for natural sceneries, on the other hand, derives from my origins, from an adolescence lived in contact with nature, a world that in my works is tinged with an ideal, uncontaminated, somewhat melancholic dimension.

Your early videos impressed me for how recurring the use of zoom is: you zoom out and show what lies around the character. It’s like a theatre curtain, revealing the stage.

It’s just like raising the curtain – a tricky mechanism because, zooming out, the frame includes unforeseen details or places you don’t expect, a solution that creates surprise and had always fascinated me. I was constantly in search of places that allowed revealing in this way, that would work in natural or architectural contexts, and could function as a framework for my stories.

How difficult is it to depict present-day youths, for you who work so much with the music that the latest generation listens to?

It is very difficult. It is an extremely composite reality, made of several subcultures, trends, and lifestyles. In the video for Liberato, for instance, I deal with it representing shared moments in settings that are not recognizable, “non-places,” contexts without geographical or temporal clues. And without any judgment whatsoever. I am interested in showing the anxiety of contemporary youth, not by explicit reasoning, but via metaphorical, evocative images. In Carlito’s Way for Tropico, I imagine Adams and Eves of our times who meet in a paradise polluted by the petrochemical industry positioned in the background. In this both wonderful and scarred context, I see the encounter of these two creatures almost mythicizing them, celebrating their bodies, their union. In the diptych Geniale / Non esiste amore a Napoli instead, I show two ways of living in a self-destructive, toxic relationship, in which you become both victim and oppressor. The violence presented in the video can be seen as realistic or purely symbolic.

How do your music videos come into being?

It is the melody, almost never the lyrics, which inspires my images: an interior, an exterior, a light, a colour... I start from there. Then, having memorised the song and its structure, I use the lyrics for keywords or sentences that suggest significant elements to me. But much depends on the song. Ovunque sarai, for example, derived from Irama's words: it is a very intimate, very personal lyric; it would have been absurd to transpose it according to a vision that was different from the one from which the song originated.

For me it is the greatest Italian video in recent years. How difficult was it to impose such a peculiar work for a song destined to become so popular?

Not so difficult as in other times: the record label people were on my side from the beginning. Irama was a bit reluctant, but in the end, he understood and embraced the project 100 per cent. It was a video where my every request was fulfilled. A unique thing – I still don't know how that could happen.

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE