Sanctuary Station

69’, 16mm trasferito su digitale, b&n, sonoro, 2024

At the presence of the curator and the director

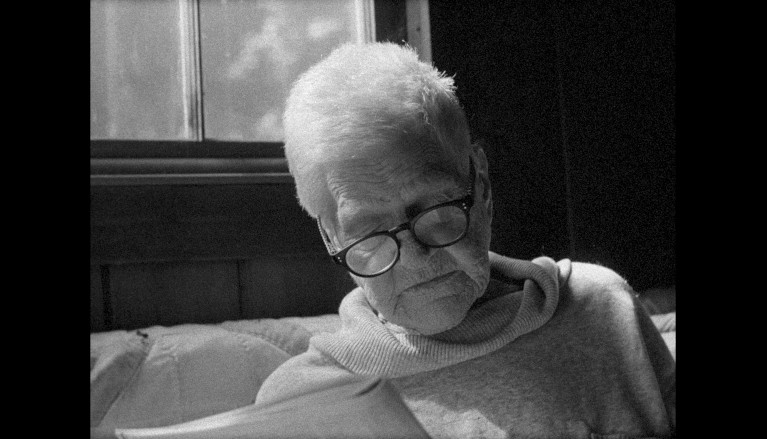

Sanctuary Station contrasts stories of deliberate solitary retreat with portraits of collective communities amid the redwood forests and remote terrains of northwestern California. Oscillations between the desire for solitude and the need for collaboration are traced through a series of encounters with women and youth who have formed intrinsic attachments to the many forms of life that surround them. These encounters are framed through the work of Mary Norbert Korte (1934-2022), a former nun who built her own cabin deep in the forest, adjacent to a former logging railroad. She relates a poetic imperative to bear witness to everything inside and out. Depictions of ongoing forest defence actions, instances of mourning, and intimate daily routines evoke cycles of life unfolding within this intricately interwoven environment.

Brigid McCaffrey is a Los Angeles-based artist and filmmaker whose work documents environments and people in states of flux. Her films explore extremes of autonomy and coexistence experienced by individuals who have distinct relationships with the land. Often taking shape as nuanced portraits, her films respond to the physical and emotional changes of their subjects while fusing representations of self and place.

She has exhibited at venues such as the Hammer Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Harvard Film Archive, the New York Film Festival - Projections, the Rotterdam International Film Festival, and the Whitechapel Gallery in London, among others. Her work was presented by Ballroom Marfa for the 2015 edition of Artists’ Film International and she was a featured artist at the 2016 Flaherty Seminar. McCaffrey was named a Guggenheim fellow in Film & Video in 2019.

by Rinaldo Censi

You spent your teenage years on the East Coast, in New York. How did you approach the moving images? Were you already interested in photography and film before attending the Bard College?

I became interested in taking photographs and printing in a darkroom as a teenager growing up in Brooklyn, NY. During this time, I also made one Super 8mm narrative film with my friends dressed as nuns attempting a crucifixion in the icy winter landscapes of the city, an attempt to toy with the imagery I gleaned from the Irish Catholic side of my family.

At Bard College, I began taking film classes where I experienced an incredible range of films within the shared space of the cinema. I was particularly excited by the poetic experimental works, diary films, and various approaches to documentary and ethnography that I encountered. (Works by Julie Murray, Jonas Mekas, Greta Snider, Kidlat Tahimik, and Trinh T. Minh-ha come to mind.) While studying with Peggy Ahwesh I made collage films using an optical printer to rephotograph and layer my grandmother's 8mm tourist films and a range of 16mm narrative and educational films I got from the public library. Through this process I began to think about travelogues, work and leisure, belonging and displacement. Working with found material in this physical way had a huge influence on my conception of film language. I also continued to study photography, primarily with An My-Lê, working with a large format camera to photograph peripheral landscapes in upstate NY.

You shot your first film on the East Coast.

After college, I made Lay Down Tracks over a two-year period in my mid-20s with a close friend, Danielle Lombardi. We were drifting between different urban and rural locations in the northeast and asking ourselves how we wanted to live, which led us to start recording audio interviews and 16mm impressionistic portraits of the people we knew that led itinerant lives. We sought out the women that appear in the film, the trucker and riverboat captain, and framed our questions around their respective experiences of work and travel. Making this film greatly deepened my interest in filming with people and navigating the nature of the relationship between the filmmaker and subject, sensing what the process of making a film could provoke personally, and documenting specificities of place and time. I wanted to get away from the east coast after making this film and found my way to CalArts.

Just like the people you filmed, you felt like moving around, travelling, experiencing new things. How did you make up your mind, and why CalArts?

I was drawn to CalArts through discovering filmmakers that grappled with the volatilities and mythologies of the American landscape such as James Benning and Deborah Stratman, among others. Billy Woodbury was screening Bless Their Little Hearts when I visited the school, and I was completely struck by its tender realism. I also connected with Betzy Bromberg, Lee Anne Schmitt, and Thom Andersen as mentors, among so many others. A proper list of all of the teachers and fellow filmmakers that affected me through my time at Calarts would be quite long, but the ongoing exchange that this community provides and still anchors me to within the non-commercial film community of Los Angeles is essential and vital to my life as a filmmaker.

Not long after beginning at Calarts, I travelled to Suriname with Ben Russell where we recorded the series of community-generated performances, reenactments, and impromptu events that compose Tjúba Tén/ The Wet Season. Ben had spent two years living in this Saramaccan community about 7 years prior to our trip, and the film structure attempts to recreate the varying degrees of understanding and experience.

In the end, you found your ‘subject’ in the landscape of California and the people who live there.

After this, I wanted to find a nearby space where I could familiarize myself with my Southern California surroundings, feeling acutely aware of my transitory status in this land. James Benning had brought a class to Castaic Lake before sunrise so that we could make our way down the natural course of the creek to its waters. When we drove up out of the ravine in the daylight and the entire construction of the lake was revealed, I was shocked and disoriented. I made Castaic Lake over a two year period of returning to this man-made reservoir at the edge of Los Angeles County where large-scale municipal infrastructure exists alongside recreational park spaces, while the wilderness seeps in through the cracks. I also completed AM/PM during this time, which initiated a long period of working in the Mojave Desert.

Can you describe the process of your work? How do you discover sites or places? Sometimes by chance? Do you study them on a map or read about them in texts? Do you go there, meet people and make site inspections? Which comes first? You said that you made Castaic Lake over a two-year period: for how long do you study the site or talk with people? You film when you already are in touch and know the people there?

After CalArts, I found myself adrift and started spending significant periods of time in the desert, camping and searching for some inspiration. Near the defunct mining town that AM/PM is set in, I came upon a contested archeological site. There, the primary tour guide shared his life trajectory, which spanned multiple industries that characterize industrial land use in the desert. I initially thought of making an essay film looking at land use through this man’s experience, but then he introduced me to Ren Lallatin, a geologist volunteering at the site. Ren's insights into the desert's geological history and its vast timescales as compared to human existence sparked a profound awareness of our fragile position. I was drawn to Ren’s deep, nuanced understanding of the desert landscape and its marginal human and natural histories, so I began joining them on various desert sojourns. Through this process, we selected sites together that highlighted Ren’s relationship to a variety of desert environments alongside the conditions of solitude brought on by their precarious living situation. As our time together grew, the filming began to incorporate aspects of our relationship.

Generally speaking, I experience periods of unrest or disquiet that provoke dilemmas about how to live, which leads me to spend time in landscapes that alter the rhythm of my own experience and to seek out individuals deeply familiar with these landscapes. The people that I connect with offer new understandings of a region and their experiences resonate with questions of personal agency. I tend to be drawn to marginal sites that attract particular and devoted interests, and to places which bear complexities of historical time. Filming may initiate some of these interactions, but may also be put aside until I develop a sense of the interplay between people and place. I sit with the material I’ve recorded and try to find ways to respond to what it lacks or instigates in form and content.

Are there directors, artists, writers that have influenced your work or that you admire? Maybe they're the ones you mention in your answer above? Are there any others? Can you talk about them?

Like many artists, I have always considered my work as part of a conversation with others, some of whom I’ve already mentioned, but the list is always growing. In recent work, for example, I am drawing inspiration from artists whose depictions of female subjectivity find parallels in their formal decisions, such as the corporeal sensibility and willingness to engage collective psychologies in Chick Strand's films. I have also been thinking about the workshops, writings, and dance constructions of Simone Forti, whose instructive strategies for performance seek out an embodied form of personal politics.

In terms of the ways that I understand how a film like Sanctuary Station incorporates an element of psychological self-portraiture, I’m reminded of the collision of figures that make up Elizabeth Hardwick’s novel Sleepless Nights, where self-description is formed through an outline of piercing relationships and personal icons, observations of self and other that shift through time.

In 1914, Ludwig Wittgenstein had a cabin built in Norway, isolated from everything, on a fjord, in walking distance from a lake. The only way to get anywhere was with a canoe that he made with his own hands. At that time, he was 25 years old. His only wish was to stay away from humans as much as he could. His is a wooden cabin, 8 by 7 mt., a little larger than the lodge Thoreau built for himself by the Walden Pond, Vermont, making its materials out of another, abandoned cabin, on the shores of another lake. He was to write Walden there.

Unlike a real home, a cabin is the kingdom of the ephemeral, the transient: for a given time of our life, we have sojourned there. Space of the temporary and of isolation from society; a refuge or shelter. These are like the places in which the people filmed by Brigid McCaffrey spend a segment of their lives: the geologist Ren Lallatin found in Paradise Spring, moving across the Mojave Desert; the poetess Mary from Sanctuary Station, who lives isolated in the forest of Mendocino County, the scene of the young activists that McCaffrey filmed; or young Azar Singh from AM/PM, who took shelter in the spaces of an abandoned mine after leaving everything behind. These are people whom Brigid McCaffrey met travelling throughout the land of California; these are the places that she chose to shoot, along with the persons who inhabit there. Prior to going westward, she had filmed other people on the East Coast – persons affected by the same restlessness, always on the move. McCaffrey’s first film was entitled Lay Down Tracks: a sort of extension of Route One USA (Robert Kramer). Or, a little gem influenced by Vertov’s kinoks: how to edit life itself.

(I can’t think of anything more relevant, to describe McCaffrey’s work and lifestyle, than the passage with which Gilles Deleuze opens the chapter On the Superiority of Anglo-American Literature: “To leave, to escape, is to trace a line. … One only discovers worlds through a long, broken flight. Anglo-American literature constantly shows these ruptures, these characters who create their line of flight, who create through a line of flight.”) [Gilles Deleuze, Claire Parnet, Dialogues II, Columbia University Press, 2007, p. 36, translator’s note]

Art of the portrait, study of landscape. Restlessness and motion. Her magnificent films move along these coordinates. The landscape is traversed, examined, scrutinized with an inward movement: it is an environment that welcomes people. It elicits various relationships with time: the time of nature and that of culture (there is the geological time, layered in the desert, and the fleeting time of those who took shelter in it; there is the century-old time of the trees in the forest, and that of the poem forming on the white sheet; or the time that took the construction of a man-made lake, as well as the time of leisure, like in the beautiful Castaic Lake). The landscape is never observed without an intent, as if to capture a cute image. It is a geological, temporal and magnetic, area. We catch the stories of those who live there – memories, emotions, knowledges. We find sediments, like the volcanic rocks that Ren finds in a site of the desert and make her hypothesize an underwater volcanic eruption, who knows how many ages ago.

Landscape makes intriguing elements surface. It mobilizes us, basically. It challenges us to wander across itself. That is what Brigid McCaffrey does with her films. They move along in perfect continuity with the process of life itself. They make part of it. To do so, you need time and patience. “Every one knows that it requires apprenticeship to see through a microscope or telescope, and to see a landscape as the geologist sees it. The idea that esthetic perception is an affair for odd moments is one reason for the backwardness of the arts among us.” [John Dewey, Art as Experience, Wideview Perigee, 1980 (1934), pp. 53-54, translator’s note]

Thus wrote the philosopher John Dewey, in his Art As Experience. It is a fine way to define McCaffrey’s films.

Rinaldo Censi

ALL SCREENINGS ARE FREE